By: Jonathan Feildstein

Some weeks ago, a friend posted a question on social media asking to list the five people “who impacted your life to make your world better.” For me, four of five were obvious and not so earth shattering: my parents, Soviet Jewish activist Natan Sharansky, and two college professors. The fifth, who I never met, raised virtual eyebrows: Abbie Hoffman. I promised my friend an explanation, and it’s timely with the release of the Netflix movie about the Chicago Seven, and the anniversary of 250,000 people gathering in Washington, DC on December 6, 1987 to protest the persecution of Soviet Jews, with which Hoffman had no connection.

In the early 1980s, early in my activism to free Soviet Jews, I came across what was then Abbie Hoffman’s latest book, “Soon to be a Major Motion Picture.” The title along, with the unique autobiographical account of his years as a Yippee and anti-Vietnam War activist a generation earlier, drew me in. I had heard of him, but never really knew much about him.

While much of Hoffman’s life and writing are not for family audiences, he engaged me as he recounted life in America at one of its most interesting and turbulent times. This coincided with my emerging activism to help get Jews out of the Soviet Union.

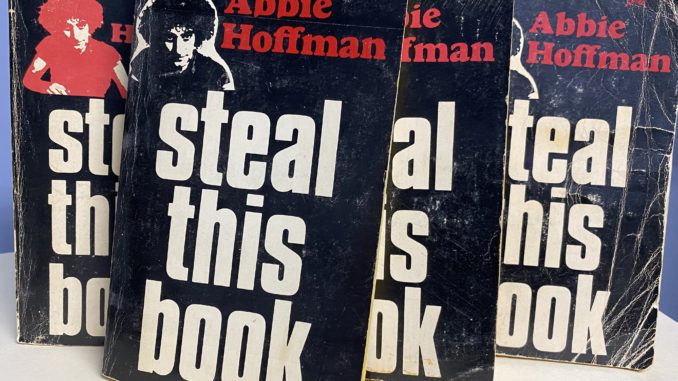

In addition to reading his autobiography, I began reading Hoffman’s other books, most notably “Steal This Book.” Because of the novelty, I started acquiring copies which I still have, and seem to be worth as much as several hundred dollars each. I’m not so sure that Hoffman would approve of my “speculating” in his books as an investment, considering “Steal This Book” was all about legal and illegal ways to “survive” in America for free, and fighting the government and corporate America.

“Soon to be a Major Motion Picture” however told the story of how he became who he was, eventually standing trial in the famous Chicago Seven spectacle before going underground, changing his identity, even undergoing plastic surgery. Hoffman’s antics, known as “guerilla theater,” are the things that struck me the most. He proudly stopped Wall St. trading for a moment, creating havoc by throwing dollar bills onto the trading floor. His account of plans to levitate the Pentagon almost made me wonder if he actually succeeded. There were many other antics and tactics that were designed to draw attention to his and his contemporaries’ agenda as they battled in one of the greatest generational wars in US history.

Reading his books, as a budding Soviet Jewry activist myself, I learned through his examples how to adapt these to my cause. I aspired to create successful protests, and generate media that would highlight these at the same time. He taught me a lot about being an effective activist, and indirectly gets credit for some of the success I had.

While Hoffman “levitated the Pentagon,” I led a protest in front of the Soviet embassy in Washington, tipping off media before of my plans to present a petition with thousands of names to free Soviet Jews. The cameras loved my unfurling the most unique petition from a 50-gallon garbage bag in the form of a paper chain, each alternating blue and white link was signed by another person.

While Abbie Hoffman taught people how to use coin operated pay phones for free, I had a list of phone numbers of Soviet embassies around the world, calling them collect at any time of day, any day of the week as there was always one open somewhere. I would ask to speak to the well-known names of Jewish prisoners of Zion, confusing and then engaging them about why they persecuted Jews, and just before they’d had enough with me, give them my finest “Let my people go” in Russian.

Where Hoffman was throwing out cash on the floor of the stock exchange, I was handing out fake programs at Soviet cultural events in the US, giving unsuspecting attendees all the details of Soviet persecution of Jews.

Albeit not trying to overthrow any government, I did rock the boat in college when I led a public grassroots campaign to get Soviet human rights leader Andrei Sakharov an honorary doctorate from Emory, both as an end in itself, as well as a means to get (Anatoly) Natan Sharansky such a degree the following year. I was called to the office of one of Emory’s top administrators and told “that’s not how we do things.” Though the honorary doctorates never materialized, I succeeded at putting Soviet human rights on the radar, even getting the university to admit a Jewish refusenick as a student in special standing.

My antics inside the USSR were much quieter, realizing that as much as Hoffman was set upon by police in Chicago’s 1968 protests, beaten up and arrested on more than one occasion, the KGB would not have been as kind to me had been caught doing what I was doing under their noses. While his book was never turned into the motion picture he suggested, I don’t have a book but did negotiate a movie contract in the 1980s. The film idea dissolved when the producer became afraid that the story would be “anti-Soviet.” God forbid. So, you’ll have to wait for the book or another producer to pick up my story for all the details including my evading the KGB and living to tell about it.

Abbie Hoffman seemed to be proud of his cultural Jewish heritage, peppering much of his language and even protests with Yiddish. I don’t know if he ever knew or cared about the plight of Jews in the USSR, or how he’d have responded to my activities. But he inspired the many of the things that I came up with as one person among a sea of hundreds of thousands or more, protesting against Soviet persecution of the Jews there.

And he’s responsible for me making one of the best investments I ever made, “Steal This Book,” so let me know if you’d like to buy one.